The enormous undersea volcano that erupted in Tonga last year was record-breaking in many regards. It generated the highest-ever recorded volcanic plume, it triggered a sonic boom that circled the globe twice, and was the most powerful natural explosion in more than a century.

Now, scientists studying the eruption say the volcanic plume created record-breaking amounts of volcanic lightning, the most intense lightning rates ever documented in Earth’s atmosphere. While the ash obscured the view, satellites and ground-based radio antennas with specialized instrument could peer through the ash and see every stage of the unfolding eruption. Over 200,000 lightning flashes were detected in the volcanic plume, more than 2,600 flashes every minute.

The researchers used high-resolution lightning data from five sources — never previously used all together — which allowed them to gain insights into the intense weather it created.

“This eruption triggered a supercharged thunderstorm, the likes of which we’ve never seen,” said Alexa Van Eaton, a volcanologist at the United States Geological Survey, and lead author of a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters.

When the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano erupted on January 15, 2022, it released a gigantic volcanic plume that rose into the mesosphere, as high as 57 kilometers (35 miles). It triggered tsunamis as high as 90 meters (300 ft), and atmospheric waves that made their way around the entire planet two times.

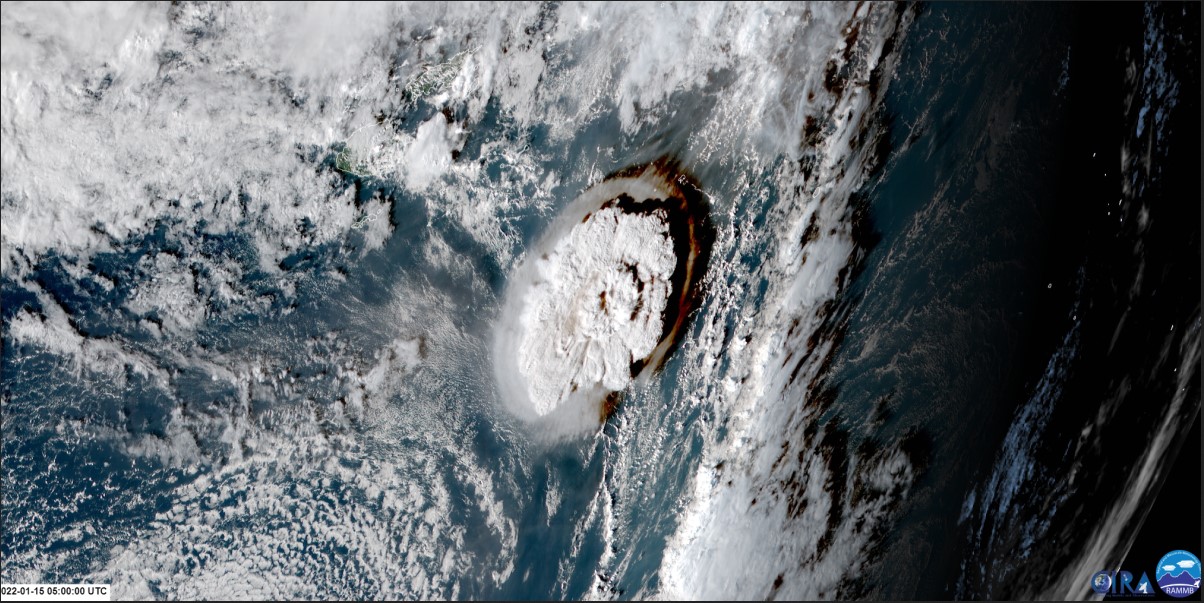

The Tonga eruption in 2022 sent ash and water into the air and created an atmospheric pressure wave that helped create an equatorial plasma bubble that disrupted satellite communications that depend on the ionosphere. Courtesy of Himawari-8 satellite.

But the eruption also formed its own weather system that created more lightning than any storm yet documented on Earth, including supercells and tropical cyclones.

“With this eruption, we discovered that volcanic plumes can create the conditions for lightning far beyond the realm of meteorological thunderstorms we’ve previously observed,” Van Eaton said in a AGU press release. “It turns out, volcanic eruptions can create more extreme lightning than any other kind of storm on Earth.”

The researchers used visible and infrared observations from two geostationary satellites: GOES-17 and Japan’s Himawari-8. GOES-17 also has a Geostationary Lightning Mapper (GLM) that uses pixel mapping to obtain the timing, location, flash area, and optical brightness of lightning. They also used a combined data set from three ground-based networks of radio antennas: the Global Lightning Data set from Vaisala, a Finnish company that conducts weather, environmental, and industrial measurements, and the Earth Networks Total Lightning Network (ENTLN), which incorporates data from the World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN).

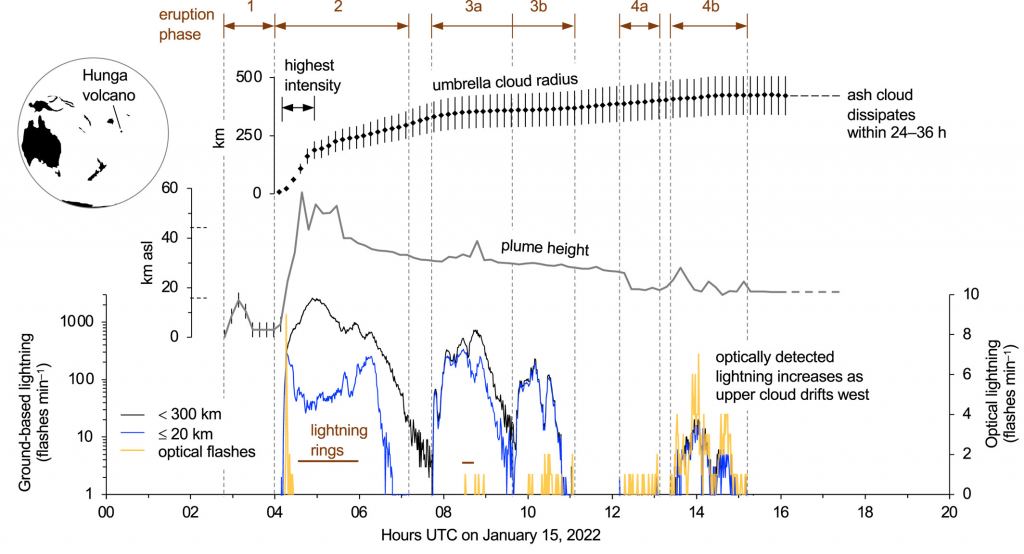

Satellite and volcanic lightning chronology of the 15 January 2022 eruption of Hunga Volcano in Tonga. Four phases of eruptive activity can be distinguished using umbrella cloud growth, maximum plume heights, and lightning rates. Credit: Van Eaton, et al, Geophysical Research Letters.

The combined power of the satellites and radio antennas detected optically bright lightning at unusually high altitudes, in regions of the volcanic cloud 20–30 km above sea level. This is activity at a height never observed before. They also observed continued and sustained electrical activity at rates not previously measured.

“The eruption lasted much longer than the hour or two initially observed,” Van Eaton said. “The January 15 activity created volcanic plumes for at least 11 hours. It was really only from looking at the lightning data that we were able to pull that out.”

The lightning provided insight into not only the duration of the eruption, but also its behavior over time. The researchers saw four distinct phases of eruptive activity, defined by plume heights and lightning rates as they waxed and waned.

There were also concentric rings of lightning, that expanded and contracted over time.

“The scale of these lightning rings blew our minds,” Van Eaton said. “We’ve never seen anything like that before, there’s nothing comparable in meteorological storms. Single lightning rings have been observed, but not multiples, and they’re tiny by comparison.”

Overall, the researchers said the remote detection of lightning contributed to a detailed timeline of this historic eruption and, more broadly, it now provides a valuable tool for monitoring and “nowcasting” hazards of explosive volcanism worldwide.

“These findings demonstrate a new tool we have to monitor volcanoes at the speed of light and help the USGS’s role to inform ash hazard advisories to aircraft,” said Van Eaton.